The Cassandra Protocol

Last week’s post brought some of the usual reactions – Why do I write about celebrity all the time? Why do I appear to be hitting friends? Given that my arguments seem in danger of being dismissed because of perceived flaws in my character and motivation, some response to personal criticism finally seems appropriate.

Very little of my time is actually spent on this matter of evangelical celebrity marketing and its baneful effects. None of my books, none of my print articles, none of my lectures, and none of my sermons have ever taken it as a major theme. And over the last few years it has been at best a secondary interest even online compared, for example, to issues of religious liberty and sexual politics.

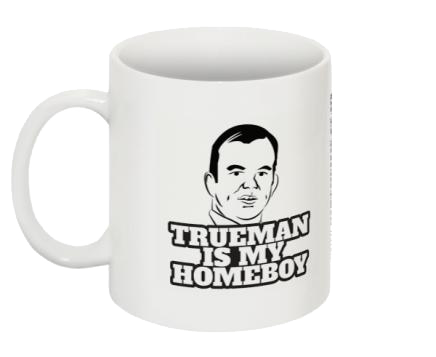

Two repeated claims have been that I too am a celebrity and that I am parasitical on the culture I criticize because I only ever write my comments via parachurch sites. As to the first, well, the ladies at head office did put my face on a coffee mug for a joke which then took on a life of its own, and numerous wits have dubbed me the anti-celebrity celebrity – a title I do wear with some sinful pride. But even if I were proved a hypocrite, that would not invalidate my arguments, only my character. And it might actually strengthen my case, being an example of the Rochefoucauldian homage that vice pays to virtue.

then took on a life of its own, and numerous wits have dubbed me the anti-celebrity celebrity – a title I do wear with some sinful pride. But even if I were proved a hypocrite, that would not invalidate my arguments, only my character. And it might actually strengthen my case, being an example of the Rochefoucauldian homage that vice pays to virtue.

As to the second criticism, that I am a parasite because I only have a parachurch platform, well, the Jewish writers at First Things would probably dispute the terminology. But even so this blog is linked to the Alliance, a parachurch ministry. Yet my (oft repeated) point has never been that parachurches in themselves are wrong. It is that parachurches are wrong when they capture that part of the Christian’s imagination which should only be occupied by the church. It is that parachurches are wrong when they come to supplant roles that really belong only to the church. And, above all, it is that those parachurch leaders are wrong who consciously leverage their status in parachurches to exert far-reaching power over others, even outside their own organizations. Two attempts of which I am aware have been made by such men to have me fired simply because of articles I have written critiquing them and their organizations. That is evil, not simply distasteful. Thankfully, the Puppet Master is nobody's puppet.

What the leaders of the celebrity parachurch world need to ask is not whether I am a wicked hypocrite but whether the crises they have faced repeatedly over the last decade are merely incidental to the culture of Big Eva or actually represent a problem which is an unavoidable part of the project. Todd Pruitt’s post on platform building would seem to indicate that at the very least Big Eva offers unfortunate opportunities and illicit temptations which no normal human being can resist. Some people are making big money out of this. Others are enjoying massive influence within our subculture simply by virtue of their status within the feudal hierarchy, not because of any ecclesiastical mandate or exceptional competence or talent they possess. Those facts are most potent – and most problematic.

So why do I criticize the world occupied by so many of my (now former?) friends? Because it is fatally flawed, has refused to acknowledge the validity of any criticism, and has proved consistently incapable of policing itself, to the increasing detriment of the church and of the theology I love. The insulated culture which it has carefully cultivated for over a decade and the behind-the-scenes bully-boy tactics it is willing to deploy against critics mean that it will almost certainly be giving birth to more scandals and crises in the next few years. If it was just about a good conference or two, there would be no problem. Who doesn’t enjoy the occasional conference? But it has become a matter of brands and of platform building, with all of the nonsense that brings with it -- the fatuous Facebook updates, the Twitter trivia, the constant, daily self-promotion on social media with only occasional flashes of any substance. It thus looks increasingly as if it is really about power and influence for their own sake and not, pace the rhetoric, for the sake of the gospel and the church And that’s a real problem.

If further disasters are to be avoided, it will be necessary to spend more time meditating on the material of the criticisms and less time mulling over the motives of the critics. But, as Ethan Edwards might say, ‘That’ll be the day!’

If further disasters are to be avoided, it will be necessary to spend more time meditating on the material of the criticisms and less time mulling over the motives of the critics. But, as Ethan Edwards might say, ‘That’ll be the day!’