The Like Culture

April 26, 2017

Derek Rishmawy wrote a thoughtful article about our online identity, something that has always been of interest to me. I began writing about the like culture in 2011, when I first started blogging an interacting on social media. I was one of those strange housewives who entered the Facebook world pretty late. I didn’t open up an account until I began blogging, and was even more timid about joining Twitter. Now, as a mom of teenagers, I’ve opened up Instagram and Snapchat accounts, not so much for my own interests, but to enter the world that they are living in.

The like button was such a mystery to me in the beginning, and I have to say that it is still something that makes me pause to ponder what it really means and why I would use it. At first, “liking” posts was very tacky to me. Could you imagine if we had a tool like this for actual conversation? Rather than commenting on the truth or value of what is said, just say like. It’s interesting how we use a positive word for an action that is so reductive.

As we become more and more accustomed to the like culture, we begin to forget to ask important, discerning questions in our online interactions. The value is in the response, or so often in the popularity person who said it, while pause and reflection is like the tree that falls in the woods when no one is there.

As we become more and more accustomed to the like culture, we begin to forget to ask important, discerning questions in our online interactions. The value is in the response, or so often in the popularity person who said it, while pause and reflection is like the tree that falls in the woods when no one is there. Likes have also become a way of dividing into online alliances. I see this with my teenagers, and I see it in the Christian bubble of social media. Instead of pursuing truth, we are often feeding into our sinful tendency to compare ourselves with others. We can easily begin to calculate the value of what we say by the number of likes we receive rather than the actual content of the post.

Additionally, the more we push that like button, the more we may feed our own illusion of power. “Aimee likes this, along with 13 other people.” Well, if Aimee likes it, it must be good. In endorsing someone else’s published material, we can create our own amateur social media status on what is cool to like. But the joke is on us. What’s really going on beneath all our playful, self-indulgent, liking banter ruse is the fact that it’s all a marketing ploy. Is it a coincidence that I liked a fitness website and now I get ads run on my page for losing weight and breast implants? I don’t know how this whole thing works with spiders and cookies and smart people who put tape over their cameras, but the market clearly gets the value of a like. Our likes are beautiful noise for companies to target us with customized ads.

The Cash Value of a Like:

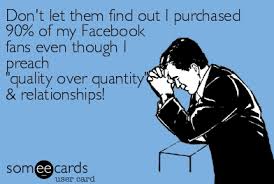

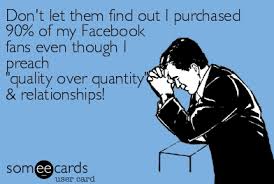

My teenagers first made me hip to the fact that some people actually buy likes, or pay for apps that will accumulate more likes for them. My heart sunk to think of teenagers objectifying their selves in such a way. Something as trivial as a like or a retweet is turned into a commodity of status. Three years ago I wrote about how likes have become a teenager’s source of validation. Is it just teenagers? I’m afraid not.

I pointed out then that the debacle in which we have pastors using church money to hire a service to manipulate the system and guarantee their books will make the NY Times best seller’s list suggests we’ve reached a whole new sophisticated like. This is what I thought about as my daughters were sharing the reality of the superficial relationships they find themselves in.  Where is the hope when we have to wonder about the character of the best-selling pastor?

Where is the hope when we have to wonder about the character of the best-selling pastor?

Where is the hope when we have to wonder about the character of the best-selling pastor?

Where is the hope when we have to wonder about the character of the best-selling pastor?What’s the integrity in a like? What’s the worth of a 14-year-old with 236 likes? What is the real value of a book on the best seller’s list? And the character of the pastor who wrote it? Or the people buying into the hype? Because there is a message being sold, but it isn’t the gospel.

I told my girls that their meaningfulness will not be measured in likes. As they were walking away, I reminded them, “Smiles are still free!” There’s a simple human gesture that communicates so much more.

And to those who think that deceiving the public by paying for likes is okay if it gets the gospel into more hands, I would like to remind you that the gospel is still free too. God doesn’t need our help to boost his status. Those of us who do write to encourage and instruct in the Christian faith should know that the value of our work won’t be measured in likes and retweets. Much of it will be offensive to the popular notions of spiritual health.

I’ve always believed smart people don’t have to tell others they’re smart, and beautiful people don’t need to advertise. They just are. Exploitation is ugly, and usually used by those lacking in the very thing they are trying to sell. Well-liked people don’t need to brag about how many friends they have, and besides, it’s not always a good thing to be well-liked. And followers are not the same a friends. So, like me or not, I’m going to say what I say. I might not attract the big guns, but I encourage the readers I do have to leave thoughtful comments, be more engaging, and even dislike in your feedback if you think I need some sharpening. And if you really do like what I have to say, please use the share button, which I think is much more helpful.

I’m still going to like things. I try to equate them with a smile, something I am generous with. I’m still going to retweet. I just want to continue to think deeper about liking motives. Be that tree that falls in the woods when no one is there and take a moment for some reflective questions. It doesn’t matter if no one hears you do it.

Can I be more engaging in this conversation? Am I just being lazy in my relationships? Is this statement true? Is it propaganda?

It’s not wrong for websites and bloggers to promote themselves. We need to if we want to bring people to our work. But I do think that sometimes we sacrifice our own classiness by feeding this whole celebrity-obsessed cultural hunger. There has to be some better ways.

*This article is an updated editing and combining of two articles I wrote in 2011 and 2014.